What do the new cycling infrastructure design standards look like?

England and Northern Ireland finally have a first set of cycling infrastructure design standards, providing local authorities and planners with a reference point from which to build safe lanes.

Safe cycling infrastructure has long been top of the cycle campaigner’s wish list, much thanks to safe lanes’ proven ability to stimulate a growth in modal share for bicycles (and now share scheme e-Scooter too). The new guidance overwrites prior detail (LTN 1/12) relating to shared use paths and will now fall under the LTN 1/20 header.

The primary reason for people choosing not to cycle, as found and cited in a 2001 TRL report, is that adults feel it too dangerous to cycle on the roads, as current legislation proposes is necessary. 62% of adults described feeling unsafe cycling on the roads.

So, what do the new design guidelines look like, what principles are they based on and can you swing a cargo bike within the permitted space as many with an eye for detail will hope?

So, what do the new design guidelines look like, what principles are they based on and can you swing a cargo bike within the permitted space as many with an eye for detail will hope?

The document begins with a twist: “Local authorities are responsible for setting design standards for their roads. This national guidance provides a recommended basis for those standards based on five overarching design principles and 22 summary principles.”

So there remains some interpretation, which is perhaps to be expected as road widths will vary drastically from town to city. As detailed in last night’s announcement, there is one key red line, painted cycle lanes without protection built in will no longer be funded by central Government.

“Where schemes are proposed for funding that do not meet these minimum criteria,

authorities will be required to justify their design choices. It still gives local authorities flexibility on design of infrastructure, but sets an objective and measurable quality threshold,” offers the document.

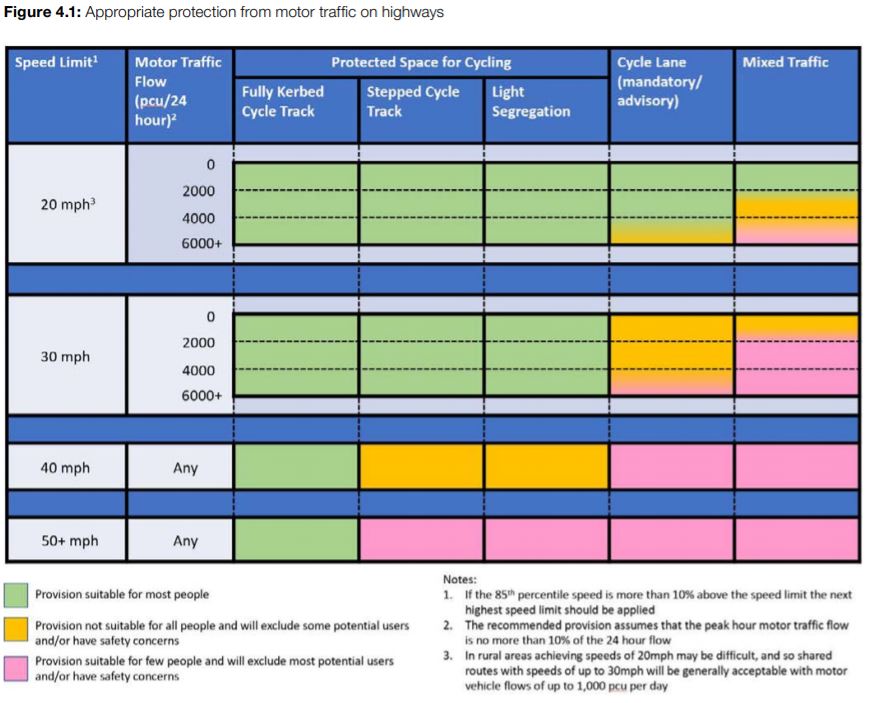

Segregation on the roads is promoted throughout, which is encouraging. Successful designs such as Blackfriars Bridge, London have been flagged, where separation on the road saw cycling traffic rise 55% post installation. What’s more, it was found that East-West and North-South cycle routes in London were moving 46% of the people in only 30% of the road space, illustrating how useful smaller mobility can be at handling city volume.

Citing the DfT’s Cycling and Walking Strategy document it is noted, contrary to perhaps popular opinion, that the installation of cycle lanes benefit nearby retail footfall by up to 40%.

It is suggested that those interpreting the Government guidance possess a qualification that builds in some assessment of effective active travel design. For example, recognition from the Institute of Highway Engineers’ Professional Certificate & Diploma in Active Travel. Courses can be found here.

The 22 Summary design principles

Primarily five objectives are to be met within the cycling infrastructure design standards document are; coherent; direct, safe, comfortable and attractive. Infrastructure must be accessible and meet the need of the vulnerable.

The full 22 read as follows:

1: Cycle infrastructure should be accessible to everyone from 8 to 80 and beyond: it should

be planned and designed for everyone. The opportunity to cycle in our towns and cities should be universal.

2: Cycles must be treated as vehicles and not as pedestrians. On urban streets, cyclists must be physically separated from pedestrians and should not share space with pedestrians. Where cycle routes cross pavements, a physically segregated track should always

be provided. At crossings and junctions, cyclists should not share the space used by

pedestrians but should be provided with a separate parallel route.

3: Cyclists must be physically separated and protected from high volume motor traffic, both at junctions and on the stretches of road between them.

4: Side street routes, if closed to through traffic to avoid rat-running, can be an alternative to segregated facilities or closures on main roads – but only if they are truly direct.

5: Cycle infrastructure should be designed for significant numbers of cyclists, and for

non-standard cycles. Our aim is that thousands of cyclists a day will use many of these schemes.

6: Consideration of the opportunities to improve provision for cycling will be an expectation of any future local highway schemes funded by Government.

7: Largely cosmetic interventions which bring few or no benefits for cycling or walking will not be funded from any cycling or walking budget.

8: Cycle infrastructure must join together, or join other facilities together by taking a holistic, connected network approach which recognises the importance of nodes, links and areas that are good for cycling.

9: Cycle parking must be included in substantial schemes, particularly in city centres, trip generators and (securely) in areas with fats where people cannot store their bikes at home.

Parking should be provided in sufficient amounts at the places where people actually want to go.

10: Schemes must be legible and understandable.

11: Schemes must be clearly and comprehensively signposted and labelled.

12: Major ‘iconic’ items, such as overbridges must form part of wider, properly thought-through schemes.

13: As important as building a route itself is maintaining it properly afterwards.

14: Surfaces must be hard, smooth, level, durable, permeable and safe in all weathers.

15: Trials can help achieve change and ensure a permanent scheme is right first time. This will avoid spending time, money and effort modifying a scheme that does not perform as anticipated.

16: Access control measures, such as chicane barriers and dismount signs, should not be used.

17: The simplest, cheapest interventions can be the most effective.

18: Cycle routes must flow, feeling direct and logical.

19: Schemes must be easy and comfortable to ride.

20: All designers of cycle schemes must experience the roads as a cyclist.

21: Schemes must be consistent.

22: When to break these principles: In rare cases, where it is absolutely unavoidable,

a short stretch of less good provision rather than jettison an entire route which is otherwise good will be appropriate. But in most instances it is not absolutely unavoidable and exceptions will be rare.

Cycling infrastructure design standards – the conclusions

The document appears to have considered in finite detail the challenges faced by cyclists, even recommending installation of wind breaks to cancel out head winds on particularly well specced routes.

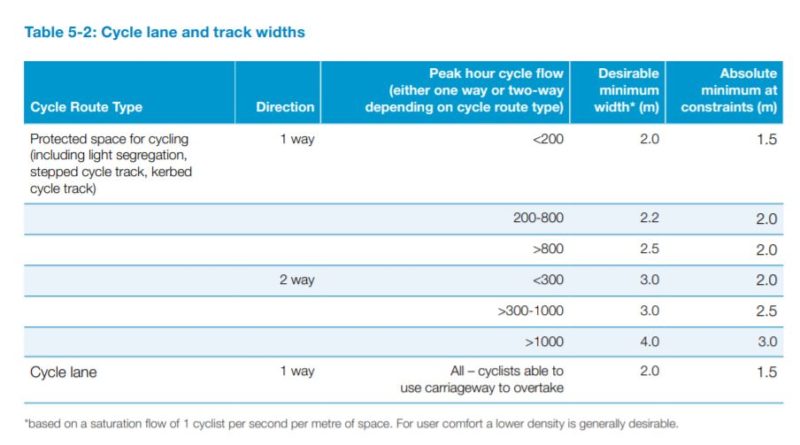

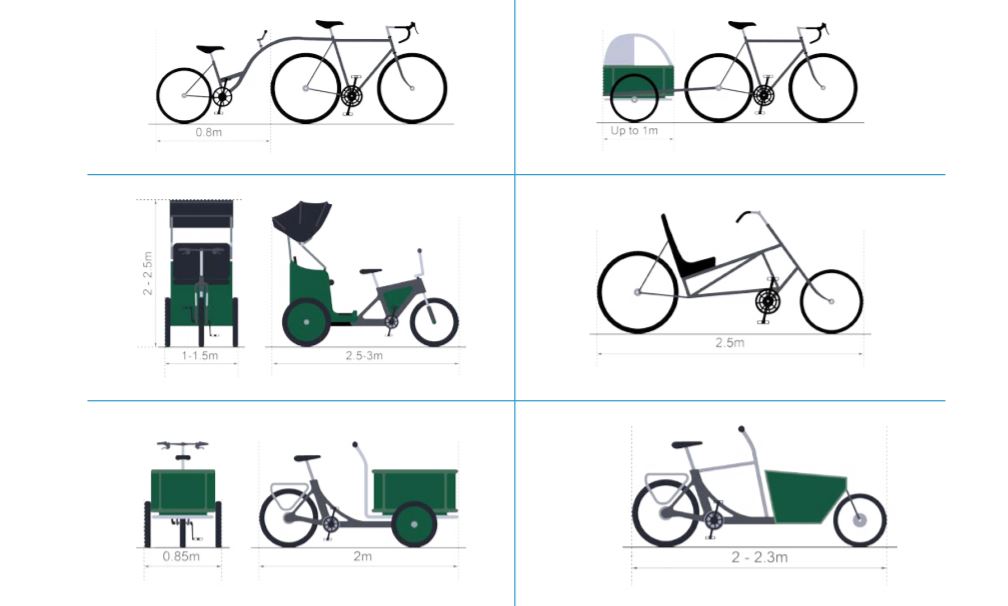

The detail most will be keen to understand relates to width recommended. Cycle path design has many factors to consider, as does wider road design. Such infrastructure will have to cope with a variety of rider volume, speeds travelled, turns in the road that cannot turn too sharply and then there’s the consideration of different types of cycle.

Cargo bikes, as they have begun to trend in the UK both for personal and business use, tend to have much wider turning circles and longer wheelbases. With companies like DHL now utilising them as part of regular inner city delivery, such vehicles must be considered as part of the transport mix.

As an example, the research found that a standard bicycle’s inner radius turning circle was 0.85 metres, compared to a tandem’s 2.25 metre inner radius.

On speed and geometry, the document writes: “Urban cycling speed averages between 10mph and 15mph but will typically vary from 5mph on an uphill gradient to around 40mph on a prolonged downhill gradient and cyclists may be capable of up to 25mph on fast unobstructed routes.

“Designers should aim to provide geometry to enable most people to proceed at a comfortable speed, typically around 20mph.”

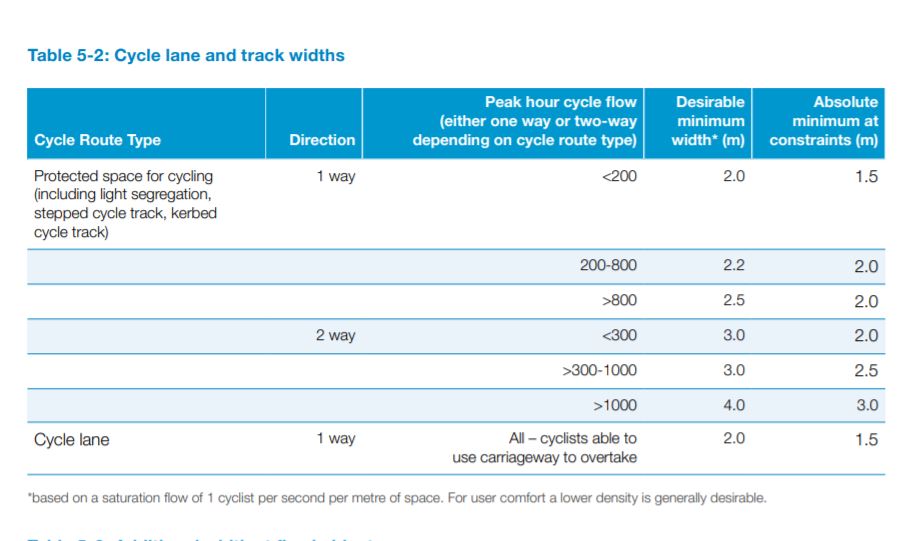

Finally, below you will find the conclusions drawn on widths as part of the guidance on cycling infrastructure design standards. An absolute minimum of 1.5 metres, rising to 3 metres for high flow two way traffic, is recommended.

Once again, to read the finite detail of the document, head here.