Comment: Why the bike industry has a tough time catching counterfeiters

Counterfeiting and fraudulent activity has long plagued the bicycle industry and  increasingly those behind such activity are using ever-more blatant methods to steal your brand’s sale. Stephen Connolly of Back Four brand protection crunches the figures in a bid to understand just how affected the bicycle industry may be, before offering a few solutions…

increasingly those behind such activity are using ever-more blatant methods to steal your brand’s sale. Stephen Connolly of Back Four brand protection crunches the figures in a bid to understand just how affected the bicycle industry may be, before offering a few solutions…

If you do a little digging around on the Internet it’s easy to find stacks of reports containing some utterly eye-watering financial details of counterfeit products being seized across the world.

Back in 2014, UK Trading Standards raided a pair of importers and seized an astonishing 34,000 fake shoes, watches, perfumes and bags with a value of £17 million.[1] Similarly in 2015 global enforcement agencies came together in an Interpol-led project called Operation Pangea, resulting in the seizure of $81 million worth of counterfeit medicines.[2] Not to be left out of the action, in 2006 it was reported that German Customs officers in Hamburg had intercepted what may even be the biggest seizure of counterfeits recorded; 117 shipping containers holding a staggering 1 million pairs of Nike trainers worth $490 million. And these are just the cases which DO get reported!

As with all areas of the shadow economies of the world exact figures are hard to come by. No one knows precisely how many drugs, guns or fakes are truly in circulation, so these kinds of anecdotes attract a lot of attention for their power to capture a snapshot of a hidden world. While it’s impossible to state with any authority quite what the counterfeit market is worth, there are still some good estimates. The comprehensive OECD/EU IPO report from 2016 “Trade in Counterfeit and Pirated Goods: Mapping the Economic Impact” maintains that:

“The results show that trade in counterfeit and pirated goods amounted to up to 2.5% of world trade in 2013. This was even higher in the EU context where counterfeit and pirated goods amounted to up to 5% of imports.”[3]

If we take the value of a particular sector then, it’s possible to extrapolate and to get a good feel for quite what the market might look like. For the cycling industry there are reports which suggest that global growth means that by 2022 the market for genuine goods will be in the region of $34.9 billion.[4] If that target actually gets met this would place a possible figure of $1.745 billion counterfeit bikes, components and accessories in circulation. It’s a sobering thought for both the industry and for those consumers who want genuine, safe and quality assured products alike.

If we take the value of a particular sector then, it’s possible to extrapolate and to get a good feel for quite what the market might look like. For the cycling industry there are reports which suggest that global growth means that by 2022 the market for genuine goods will be in the region of $34.9 billion.[4] If that target actually gets met this would place a possible figure of $1.745 billion counterfeit bikes, components and accessories in circulation. It’s a sobering thought for both the industry and for those consumers who want genuine, safe and quality assured products alike.

Ask yourself this question though, when was the last time you heard about a seizure of goods relating to bicycles which even vaguely rivalled the kind of case mentioned earlier? The truth is that you probably haven’t. Even for those of us who work in the anti-counterfeiting world there is a notable lack of activity for the cycling industry. The question is, why?

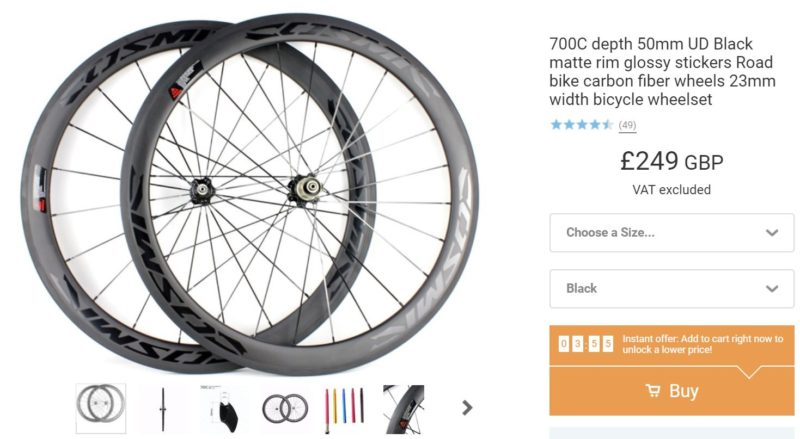

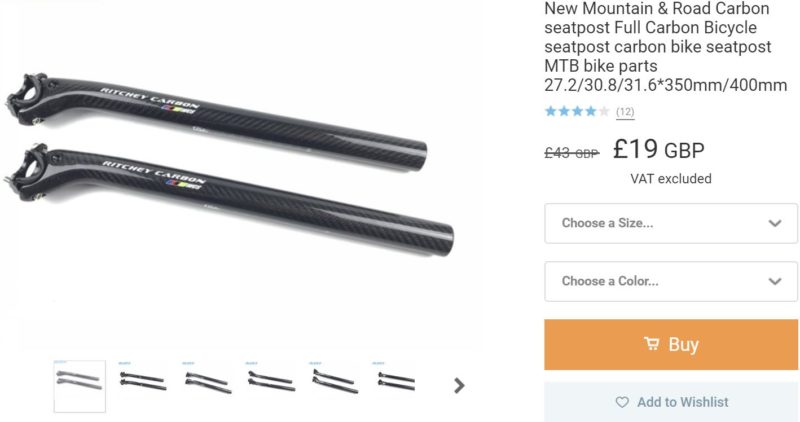

It seems to me that the cycling world has two main problems when it comes to combatting fakes. First, one big problem is the technical specificity of cycling. The highly detailed nature of carbon fibre frames, for example (and whether the tensile elasticity of their modulus is of a genuine gigapascal level), is enough to have most of us lay folk running for the hills. Technical details of this kind can be bewildering for enforcement officers and consumers to point where they just don’t know how to begin with telling the real from the fake. As a result, seizures of trainers and handbags which aren’t all that well rendered can be much easier to spot.

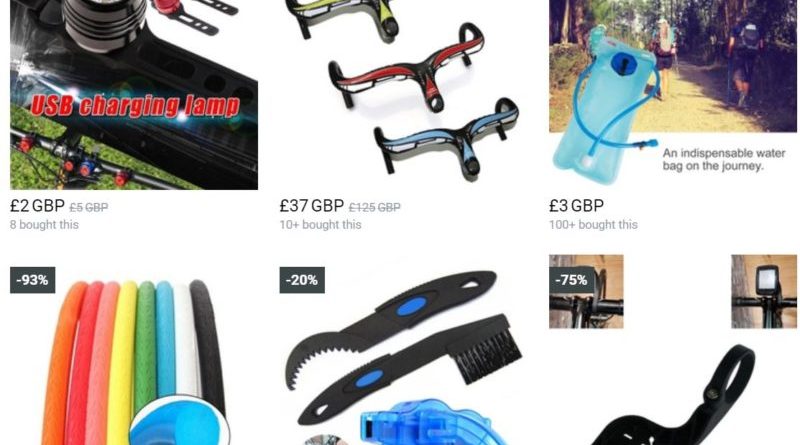

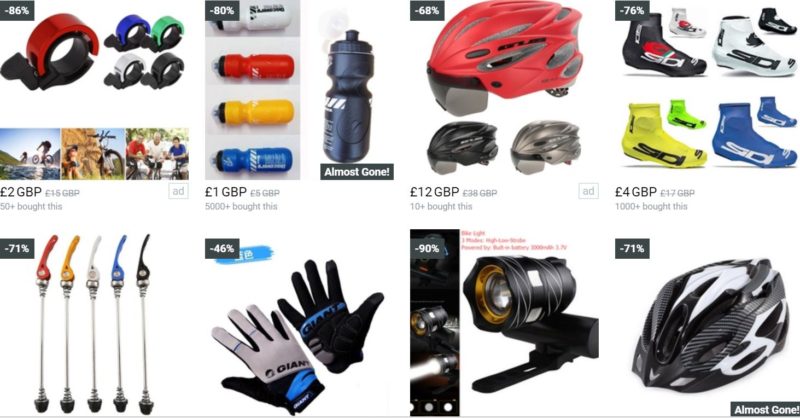

Does that mean that there isn’t a trade in counterfeit cycles? Certainly not. The much derided “Chinarello” copies of the famous Italian brand are legion across Chinese websites. Likewise, other reports on counterfeits in the cycling world have outlined in detail quite how the Chinese counterfeiting machine works with regard to some of the areas of concern to cyclists.

In March of 2016 the World Federation of Sporting Goods held a joint operation targeting the cycling world alongside Italian counterfeiting investigators. The result was some €9 million of hooky goods removed from circulation.

It may be then that the technical nature of bicycles may actively work in the favour of counterfeiters by impeding enforcement against them and allowing the trade online and in person to continue. In addition to this though, it may also be that the cycling industry’s unique problem is its own uniqueness.

Effective anti-counterfeiting activity relies on a number of factors but chief among them is the brand’s possession of the strongest possible Intellectual Property (IP). Registering and maintaining trade marks, design rights and patents can be a complicated business and often the enforcement against counterfeiters really does come down to proving that the brand owns a relevant mark which is being infringed in a deceptive and intentional way. For big brands such as Nike, Louis Vuitton and others it’s possible to achieve phenomenal results in terms of seizures because their IP rights are both widely known but also consolidated. They are single operations where the IP is owned by a set company, which will also usually have a dedicated legal or brand protection function within the business. From this perspective it couldn’t be easier for Trading Standards, Customs or the Police to find out who they should contact if they come across goods which may not be genuine.

The unique situation of the cycling industry, however, is the question of who owns what IP rights, what exactly is being infringed and who is responsible for working to protect the brand and the consumer? An expensive bike set-up may be built from a range of different brands; from the frame to the brake pads, from the pedals right up to la casquette perched atop the head of the fixie riding courier, cycles are a complicated mass of different brands and signatures. What’s more, the frame might be manufactured by a Chinese factory on behalf of an American company and imported to Europe through a Turkish shipping line. This situation can be a difficult one because enforcement officers don’t know who to turn to for the expertise they require to say something is both counterfeit and is also infringing somebody’s rights. Not only does it make it difficult for enforcement agents, leading to a lack of these high profile anecdotal seizures, but the failure to stop this trade means that it also creates a distinct lack of trust among consumers.

But if the picture seems a little gloomy the news isn’t all bad. Historically, the brand protection for the football industry in the UK has been an exercise in stopping exactly this kind of mixed messaging. When the FA Premier League first decided to institute a co-ordinated project called the ACP (Anti-Counterfeiting Programme) on behalf of all their clubs there were similar concerns about who owned all the rights and products which would potentially need protecting. Football clubs own a range of IP rights, which they then license to manufacturers, distributors and other trusted commercial partners. The number of factories, warehouses, shipping agents, sales departments and retailers is enough to give even Clarke Carlisle (ICYMI, he once won Countdown) a headache. This isn’t even to mention the added complications created by kit manufacturers, players, agents and a whole host of other image rights holders. Football Clubs also don’t exist in a vacuum either, they depend on each for competition, without which they couldn’t exist. As a result, both genuine and counterfeit products tend to be sold together with more than one club present. This lack of homogeneity could have meant that the presence of counterfeit merchandise went unchecked because no one knew who to turn to for the relevant co-ordinated opinion.

The ACP provides this consolidated opinion and takes action on behalf of the league as a whole, this is its great value. By pulling together the resources of all the different experts it is possible to provide a single perspective after all. When you have a single point of contact for both the public and for enforcement it becomes easier to react quickly, which, as a result, can ensure that counterfeiters face the relevant punishment. The provision of education, conferences which focus on IP rights and genuine products, brand protection guides, online removals, fan engagement, all these things are possible for a mixed industry such as cycling too. No problem is insurmountable, all it requires is that people and companies (even natural competitors) work together in order to be as inclusive and communicative as possible. For every industry it is possible to shine a light on the darker corners of commerce. When the ACP began there were people on the outside who said that the competition between brands would be too intense, that they would be unwilling to work together and this would result in a lack of progress.

They were wrong.

To prove my point? It seems fitting to end with an anecdote about a seizure. In 2015 Ghanaian Customs officers stopped a seizure of 1 million Arsenal and Chelsea branded condoms which had been shipped from China.[5] It turns out poor quality rubber isn’t just a problem for the cycling industry.

[2] https://www.interpol.int/News-and-media/News/2015/N2015-082

[3] OECD/EUIPO (2016), Trade in Counterfeit and Pirated Goods: Mapping the Economic Impact, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[4] Growth Opportunities in the Global Bicycle Industry 2017-2022: Trends, Forecast, and Opportunity Analysis https://www.reportlinker.com/p04837543/Growth-Opportunities-in-the-Global-Bicycle-Industry.html

[5] https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/fake-arsenal-chelsea-condoms-seized-6478631