‘Lost’ infrastructure project uncovers 100+ cycle tracks built by (1930s) UK Government

Research on a forgotten 1930s network of Dutch-inspired cycleways across the UK — partly rediscovered with the help of Google Street View — has been published on an expansive multi-media website, BritishCycleTracks.com.

Between 1934 and 1945, the Ministry of Transport paid local authorities to build 100+ “cycle tracks” modelled on the cycleways of the Netherlands. BritishCycleTracks.com documents why they were built, how they were used, and why they faded from memory.

Urban planning experts have evaluated the best period cycle tracks for revamping. Leicester City Council used the research as part of its successful bid for part of a £2.2 million Department-for-Transport-funded renovation project. With the launch of the website, more local authorities could use the information provided to bid for funding to rescue their tracks.

The historical research — partly paid for with grants from the Department for Transport and others — was carried out over seven years by journalist and historian Carlton Reid. His 120,000-word study forms the backbone of the website, which includes then-and-now swipeable maps and images.

RESEARCH. RESCUE. RENOVATE.

The research uncovered more than one hundred period cycle tracks. Much of the original detective work was done by searching on Google Street View. Nearly 500 miles of routes have been plotted on the project’s online map.

Today, many of the cycle tracks are hidden in plain sight. Others are buried. Several have remained in use as cycle tracks, but there is little local knowledge that the infrastructure is more than 80 years old.

Space for cycling, which many planners and politicians often say isn’t there, has been there — often unknown and neglected — for nearly a century, said project partner John Dales of Urban Movement of London. His company produced a report for the Department for Transport that evaluated the upgrading potential of twelve period cycle tracks and included engineering drawings. This report is on the new website.

Of the twelve schemes for which Urban Movement provided engineering diagrams, Mr Dales said most of the local authorities concerned were highly interested in using this (expensive but free to them) design work in future bids for funding from Active Travel England.

Reid’s project has had backing from experts such as former transport secretary Lord Young of Cookham.

Lord Young wrote to a transport minister “this 1930s cycleways project looks to be excellent value for money as it could resurrect already-built infrastructure at a fraction of the cost of new infrastructure.”

Many of Britain’s 1930s-era cycle tracks were “lost” or forgotten about within ten years of their construction.

By the 1960s not even officials within the Ministry of Transport knew that the UK government had majority-paid for 500 miles of Dutch-style cycleways, mostly built beside the new arterial roads of the 1930s and 1940s.

Urban Movement assessed the modern utility of twelve of these cycle tracks, to bring several of them back to life by rediscovery, renovation and — with local authority buy-in — meshing into modern urban and edge-of-urban networks.

- Links Road, Blyth, Northumberland

- The Links, Whitley Bay, North Tyneside 3. Euxton Lane, Euxton/Chorley, Lancashire 4. Formby Bypass, Sefton, Merseyside 5. Harpfield Road, Stoke-on-Trent 6. Arnold Road, Nottingham 7. Raynesway, Derby 8. Melton Road, Leicester 9. Kenilworth Road, Coventry 10. Marston Road, Oxford 11. Uxbridge Road, Hayes, Hillingdon 12. Mickleham Bypass, Surrey

While more than one hundred schemes have been identified and recorded, not all should or could be rescued — some were “white elephants” at the time, and many remain so today.

There are many benefits — to motorists, cyclists, and pedestrians — to having protected cycleways, but very often, it is claimed that there is no space to provide such separated infrastructure. This project has found that there are many period cycle tracks where the space was made available and, in many cases, is still there but often misidentified or hidden in plain sight.

Cyclists and pedestrians benefit from protection, and motorists benefit from potentially freer-flowing roads, an outcome lobbied for by period motorists.

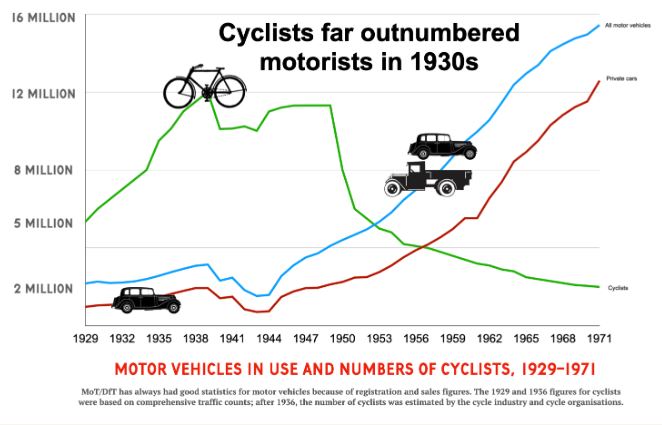

Between 1930 and 1935, the numbers of cyclists doubled in the UK, and officials worried that the explosion in cycle use would reduce the utility of motoring. By 1939, there were twelve million cyclists and just two million motorists. Cycle use plummeted after 1949, leading to the ossification of the MoT’s ambitious-for-the-time cycle route network.