INTERVIEW: Silca CEO on innovation and product that avoids landfill as long as possible

After an engineering career covering different industries, and a stellar stint as Technical Director at Zipp, Josh Poertner grabbed the opportunity to buy the – at the time – troubled Italian brand Silca in 2014. Since then, Poertner and his team have combined Silca’s heritage with technical innovation, creating some eye-catching and exceedingly popular products, as well as his less heard about but at the cutting-edge, Aeromind. CyclingIndustry.News quizzes Poertner on picking up Silca, the state of the industry and how cycling businesses need to make sure they’re asking the right questions…

We open our chat with Josh Poertner, one of the industry’s best known engineering minds, with a question about Eurobike, which Silca did not exhibit at this year, opting to spend out on visiting its international distributors individually instead.

“It makes sense to have more consumer days,” Poertner tells CyclingIndustry.News. “Certainly the trade shows in the US have gone predominantly consumer. And I would say for us, they’re far more valuable because nobody talks to the consumer like the brand.

“I can completely see what Eurobike is doing and I think it makes a ton of sense for the German market, but I think it definitely makes it a little bit less valuable internationally than it was before. With those big consumers days, nothing gets done. You’re not having a high quality sit down with anybody in the midst of that chaos.”

Then talk turned to Silca…

From an outsider looking in, it seems like your company’s super focused on creating innovative products and that philosophy seems to be almost baked into the brand – I think it was one of the first companies to put gauges on pumps? Do you think that’s fair to say innovation is intrinsic to Silca?

Yeah, hopefully. The company in its beginning was very innovative. And by the time I got hold of the brand that was gone and for a long time, I think. The founder of the company was an aerospace engineer, Felice Sacchi, and Silca was doing really innovative stuff. He was one of the first working in celluloid, before plastic existed. And so that’s where all those lightweight and frame pumps came from. They cornered the market back in the day because they were so light in a period where everything else was using steel. It was extremely innovative and then he passed.

Pre-World War Two, Silca was making celluloid products for brands like Ducati and Piaggio and all the motorcycle companies. At one point every Fiat had a Silca pump in the car. In World War Two, Mussolini nationalised Silca. We don’t really know much about that period of time other than the factory was levelled by allied bombing. Then when the company came back, there was no money for cars and motorcycles so bicycles were the primary business.

Then you get to the ‘60s, when Silca launched the Pista pump. And the next big innovation was 1989, the Superpista pump, which was a taller piston with a bigger handle… From then to when they were really struggling there was not a whole lot else. They lost their export advantage when the Lira changed into the Euro and there was a lot of stuff like that happening.

But I really saw a vision for it. My background is extremely technical and I really saw an opportunity to blend this heritage quality, classic, old-world brand that was innovative way back in the day. And to rebuild that ethos and quality and really merge that with the tech that I love so much. So that’s kind of baked into me.

I had 15 years with Zipp making – and this always gets construed wrong when I say it – but these were basically disposable products, right? The whole point of race wheel development is to develop wheels that are faster than last year’s wheels, right? I mean, you’re endlessly obsoleting yourself and trying to make the next lighter, better, whatever, faster thing. And you know, that’s super fun for years. And then, you know, it gets less fun and you think, gosh, you would see stuff I had done 10 years prior and think, that needs to be in a landfill and think, Oh, God, that’s terrible. Everything I’ve ever made is in a landfill somewhere.

So being able to pick up a brand like Silca really flipped that on its head. I can do all the tech stuff I want and really bring some innovation and technology, but also keep this ethos of wanting it to live forever. Or as long as possible. I think s me of that is from our marketing department but I also think some of that is legitimate. I think we’ve done a pretty good job.

When you’re looking at developing new ranges, do you try and focus on particular sectors that are doing well at the time, say the gravel scene? Or is it sort of a bit more organic than that and your R&D team looking at different areas all the time?

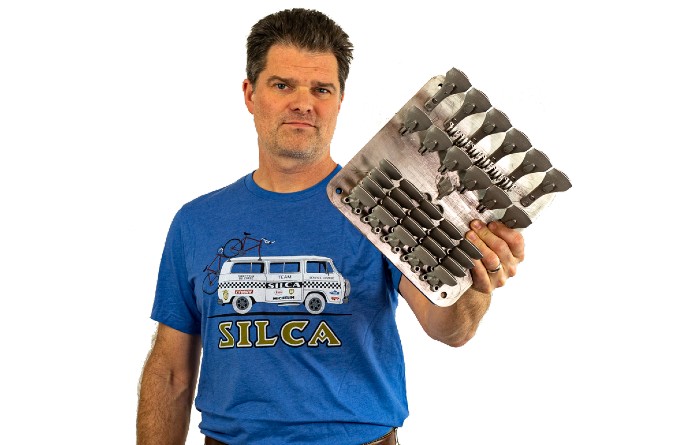

The almost untold story of modern Silca is how we bought the brand. When I left Zipp SRAM we had to start a company to go to Italy and buy the brand. The company was in bankruptcy and the government was taking all the assets. So the only thing to buy was literally the trademark.

So, we formed a company here in the Stat s, called Aeromind, that we then went to Italy and bought the Silca trademark and started operating as Silca. Pretty quickly, with me leaving Zipp, everybody and their brother wanted designs for aerofoils, or frames, or handlebars, or wheels.

And in the early years, I had no desire to do that. I had a company to build from scratch. Day one we had a piece of paper with a trademark on it, a blank laptop and it was a case of: “I’ve got a lot of work to do, and it’s not making things for you”.

But as time went on, those requests got louder and became more lucrative. And so, Aeromind currently works with five or six World Tour teams. We cover wind tunnel development, rider positioning, field testing, tyre rolling resistance and equipment optimisation. If you’ve listened to our podcasts it’s kind of mentioned here and there. We don’t really name names, and we don’t talk too much about it. And some of the stuff we do is really quite interesting. In the last Olympic cycle, we actually had a national federation in a big argument with their equipment supplier. They agreed jointly to hire us as a neutral third party. We did a big independent analysis then presented the data back to them. And that way, it’s not two people shouting at each other. It’s about as neutral as it gets, I don’t care what the answer is.

I think as a result of living in that world we get a ton of ideas and a ton of requests. Then we see an opportunity where mechanics are getting really frustrated with something, we wonder if we can do that. Like our 3D printed titanium tools. We get a lot of shit for those things being so expensive. But when you’re talking to the CEO of a World Tour team, and they say they’re going to spend €25,000 on luggage fees this year, you think “What if I could take two kilos out of a mechanic’s toolbox?

Could I get it under the weight?” So you’re building a strategy around looking at what the lightest tools are. And then you identify a point like: “I could 3D print these super-light and hollow”. Now we actually have a couple of teams for which we’ve built toolbox and flight box strategies for. You’ve got consumers saying that’s the dumbest thing ever. And then you got people over here who would say: “Oh my God, you saved me 1,000s of Euros every year in these stupid luggage fees.” So, yeah we get opportunities we pick up from working with the team.

I really believe that most of the companies in our industry – because it’s an enthusiast industry – are really sincere. They’re telling the truth as they know it and they’re really trying hard to get the right answer. But I think the opportunity is there because most of those companies are getting the right answer to the wrong question. That’s a big way we run our product development design.

Our company doesn’t start with finding the answer. I want to spend the first three months of a project really digging into what the hell’s the right question? I think a lot of times you end up finding completely different answers if you can rephrase it. think that’s where I’ve been fortunate with my 30-year career. I’ve worked in aerospace and auto racing…

I feel really fortunate to have this really wide experience and a very broad range of contacts that you can pull into these things. You can ask them: “Hey, our industry looks at this problem like this. But I don’t think that’s right. What am I missing?” and they might tell you: “In our industry we think of it this way” or you just get these different viewpoints.

Take handlebar tape, right? Every handlebar tape company on Earth uses the word ‘damping’ and it’s clear that not a lot of them actually know what the word means.

In all the tyre resistance work we’re doing we found that you want as little damping as possible in the system, right? You want low hysteresis. And so we start thinking, if low hysteresis tyres are much faster and much more responsive and handle better. So when you start studying you realise you don’t

want damping elsewhere. We really started looking at that.

We found that our foam technology came from Nike or Oakley, or the companies that do those things for those companies, and we merge it all together. We came up with handlebar tape I think four years ago and people were like, what the hell? That’s expensive, why is a pump company making bar tape? And Tour Magazine did its ‘22 brands shoot out; and we just destroyed the field. I think we won four out of five categories.

Now I could point to probably five or six companies who have made very, very advanced replicas of our product. If you are a company that believes in damping and you’re using highly dampening foam, that’s your thing. You have legitimately solved that question. Right? But we’ve now proven that that was the wrong question. For me, that’s when stuff gets exciting.

About every two years, we’ll step into some new category. And I don’t think we’ve ever walked into a category that we weren’t instantly dominating, technically. And totally by design. If I can’t show up and really own something new, then it’s just not worth it. It’s not fun to show up and be third or fifth or last.

On top of all the stuff you see, there’s absolutely like a graveyard of stuff that we’re just not going to do. Or there’s companies that are that have answered the right question, in the right way already. The world doesn’t need more copycats. That’s for sure.

Silca took over Crud Cloth recently. Are you looking to aggressively grow that in terms of ranges or what are your plans for that?

Crud Cloth was an interesting one. We’ve bought a handful of companies now and a couple that nobody knows about. Crud Cloth came to us. This really smart, clever inventor created this product, loved his product – it was one of the best interactions I’ve had with a small start-up inventor. He quickly knew that he didn’t want to run a company. He’s a product guy, he doesn’t want employees.

We are a technology company at heart and Crud Cloth might seem like a glorified shower wipe, but that’s really some pretty high technology in there. And then the patent is fascinating.

One of the things hidden in plain sight with wipes is they’re usually pre-moistened and the towel is typically pretty crappy. But because it’s pre-moistened the biggest challenge for making a product like that isn’t cleaning the body of the person who uses it, it’s keeping it from growing mould on a shelf until that person buys it.

So if you look at a wet wipe or whatever, on average there are 20-23 ingredients, seven of which are some sort of algaecide? There’s a lot of pretty bad stuff in there. And that’s why when you use them, they leave like a sticky residue. No matter how much fragrance they put in it, it always smells a little bit ‘off’. The patent behind Crud Cloth is that having the liquid in the pod separate, you can use UV light to sterilise everything. And so because everything’s sterilised a couple times along the process using UV light, you’d have had no need for any of those other chemicals in there. If you look at the back of a Crud Cloth, there are just three ingredients. It’s water, a coconut-based surfactant and an essential oil for fragrance.

This is a significantly better way of making this product. But the technology behind that is a real door opener for a whole lot of other things. You can let your mind go wild and think of half a dozen other things you could do with this. Crud Cloth is a fun product. It has a cult following, it’s growing. But really, it’s a technology play. I would say, expect to see that technology used in unexpected ways.

Can we talk specifically about the UK, where you work with distributor Saddleback: Have you got a perspective on how the UK market is doing in comparison with, say, the USA at the moment? We’ve got overstocks and a tough economic market, what’s your take on it?

From the outside, wow. I mean, Brexit, you guys just really screwed that one up. And that’s coming from an American. We watched you make that mistake, and then we brought in Trump!

The UK market is a challenge on a number of fronts. Brexit has made import/export an absolute nightmare. On top of that you’ve got massive inflation and energy prices which is squeezing, everybody, businesses and consumers. With the price of electricity, that’s a lot of money sucked out of a business or out of household income.

Our industry is not always great at business, to be honest, when it comes to planning. There was a very well-known industry executive who I won’t name but from one of the biggest companies. He gave a digital talk at the Digital Taipei Show in 2021, and he showed this graph showing, essentially, the current rate of growth lasting till 2028. I remember at the time thinking there’s no way. I’m an engineer by background and a math guy since childhood. You do some quick calculations and the current growth at the time continuing to 2028 and for the whole world… I think you could disprove that on a napkin.

I think the ordering behaviour was bad. Yes, the supply chain issues were hard. And then that whiplash effect was absolutely real. I’m very fortunate to have some pretty amazing business mentors. They’re very experienced folks who work in multiple industries, and who have experience in cycling. We talked weekly in that period about decisions and ordering purchasing behaviour. I think we weathered it more than most. We made mistakes, but you look at some of the mistakes that people made, it was crazy.

It’s hard, when you’re making more mon y than you’ve ever made… for a while there it felt like “My God, I can sell anything I can get”. But you really do have to step outside yourself and just do some quick math and say: “All my competitors are behaving just like this too and the population is only so big.” And once we had the Covid vaccines you realise that this is transitory. Covid won’t be a 10-year plague. It’s going to die off and that will change behaviour again.

I’m a consumer too and what do I want to do coming out of Covid? I want to go places and travel and spend money on experiences so I’m not going to buy another bike this year, I’m not going to buy three more bib shorts.

I tell my team all the time, we just have to make more good decisions than bad ones. But we have to do that every day. We could have sold twice as much of x back in the August of 2021 – if I could get it. But, we’re better off to with a reasonable inventory situation today.

I think it’s gonna take one to two years to get back to normal. If you look at just the storage fees… I’ve got a friend at a big company and he said they’re spending about a million dollars a month to store their product worldwide. That’s got to be a lot of product, and then how long does it take to get that inventory down? A long time. I know certain long lead time industries like clothing are really hurting.

Where you’re putting your fabric order in nine months out. That one’s almost an impossible problem. Because the lead times are so long, you’re making decisions in 2021 for your 2023 lines. The other thing that was happening if you go far enough back in the supply chains was the raw material manufacturers who could sell everything they could make were forcing larger orders to guarantee you a place in line.

The tubing suppliers knew they could sell anywhere in the world for twice the price because people are building houses like crazy. So they were going to sell it to wherever they can get the most money and they wanted huge orders at crazy prices. With lead times of nine to 12 months, you almost have to be a seer of the future! We definitely got some things wrong and I’d say the situation is going to hurt for at least another year. Maybe two.

This article originally ran in CyclingIndustry News’ issue #4 of 2023. You can read the entire magazine in our archive and you can subscribe to the magazine here (for free if you are within the cycling trade).