85% of cycling increase can be attributed to new infrastructure, claims Cambridge Uni study

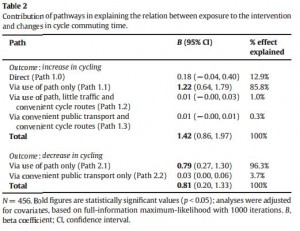

A new report has suggested that “85 percent of the effect on increasing cycling was explained by use of the infrastructure”.

Funded by the Medical Research Council and written by researchers at the University of Cambridge, the authors utilised available data from natural experiment studies in Cambridge, analysing people’s exposure to new infrastructure. The researchers focused on:

- Perceptions of the route to work

- Theory of planned behaviour

- self reported use of infrastructure

Noting in its introduction the health benefits brought with an increase in active travel – something a World Health Organisation report recommended to Governments worldwide earlier this week – the paper pointed to reduced healthcare costs as one key positive to be taken from infrastructure successes.

A previous BMJ study in 2015 concluded that fresh active travel corridors designed to increase the connectivity of local areas were linked with changes in environmental perceptions. However, the effect of such routes on active travel behaviour was largely “explained by use of the new infrastructure, not by changes in perceptions.”

Participants in this new study reported all of the commuting journeys and the transport used over a seven day period. In an interesting twist, those who cycled any part of their journey were asked to report on average time taken, something which appears to have decreased with dedicated cycling infrastructure, resulting in less time spent in the saddle overall.

On the shortened journey time the researchers said: “We used a measure of self-reported changes in the time spent cycling, and the new infrastructure may have reduced the actual or perceived cycling time for some commuters. Although exposure to the busway did not significantly shorten the route to work in the overall sample (Heinen et al., 2015a), for some commuters it may have provided a more efficient cycling route, with fewer junctions and consequently higher speeds. Consequences of this kind may explain why we observed divergent effects on cycle commuting time in our sample.”

“We are only just beginning to understand the pathways by which environmental changes may bring about changes in physical activity behaviours,” said the paper in its interpretation of findings. “To conclude, we found that exposure to the intervention led to an overall increase in the time spent cycling on the commute, mainly through use of the new infrastructure for cycling. This increases the likelihood that the observed effect was truly causally associated with the intervention.”

Before reaching its summary on cycling, the paper does add that high-quality bus services aimed at commuters might prove an attractive alternative for people who prefer not to use the car.

In the study’s conclusion, the researchers summarised that the findings did “strengthen the causal argument that changing the environment led to changes in health-related behaviour, via use of the new infrastructure, but also show how some commuters may have spent less time cycling as a result.”

If health benefits are not enough to convince city planners, perhaps the numerous economic benefits revealed in a recent DfT commissioned report might sway some spend.

Read the full report here.

Related: Six cities where cycling is taking modal share from cars