“Not even close” – European cities failing on green mobility transition, says study

A new study from the Clean Cities Campaign has outlined just how far off the pace European cities are when it comes to meeting targets on climate-friendly mobility forms.

“No major European city is fully on track to move its citizens onto more climate-friendly forms of transport by 2030, threatening to undermine a vital component of the EU’s efforts to cut greenhouse gases,” starts the campaign in its statement.

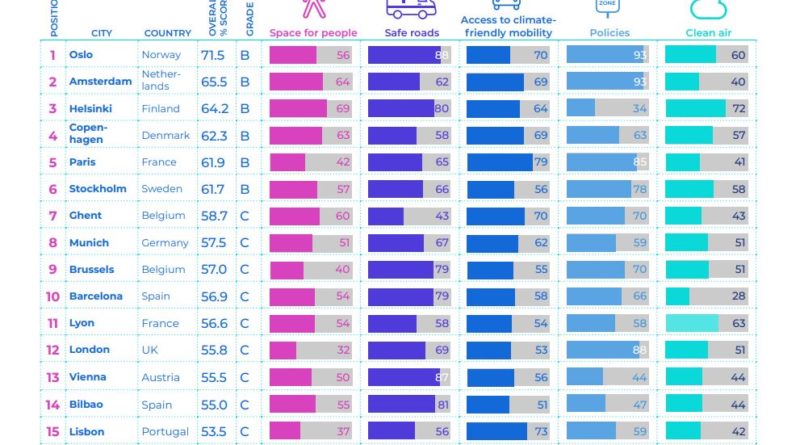

Scored across five metrics – Space for People, Safe Roads, Access to climate-friendly mobility, Policies and Clean Air – the leaders are predictably Nordic.

Oslo, Amsterdam, Helsinki and Copenhagen make up the top four, while Paris rounds out the top five thanks to its sustained campaign of developments in the Covid era. Each city is graded with both a letter and a percentage score indicating how close to targets each is.

36 European cities are measured in the report, which the lobby group will now use to further its goal is to drive city leaders to reach Zero-emissions from mobility by the turn of the decade.

“Our report should be a wake-up call to city leaders across Europe,” said Barbara Stoll, Director of the Clean Cities Campaign. “Cities need to take much more serious action to radically reduce emissions from transport and they must set a clear vision, timeline, and a pathway for fully transitioning to active, shared, and electric mobility by 2030”.

UK cities London, Birmingham, Manchester and Edinburgh feature in the analysis, ranking 12th (C grade), 17th (C grade), 30th (D grade) and 31st (D grade), respectively. The lowest-ranked city in the report was Naples with 37.8%, just below Krakow with 37.9%.

While London graded well on policy direction, space for people offset any positives and ranked among the worst in Europe. Manchester, widely seen as a progressive space in active travel terms, scored similarly low on space for people, poorly on policies and access to climate mobility, but did better when safe road conditions were assessed.

With mobility in cities representing 23% of the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions it is the only sector to see its output worsen since 1990. Nearly 75% of Europeans live in these city spaces.

The authors are optimistic that a window of opportunity remains to hit targets, despite Covid-19 measures being scaled back. Much of the infrastructure laid for active travel means during the pandemic has demonstrated return on investment, growing cycling rates by between 11 and 48%, on average in 100 EU cities.

Stoll said: “This benchmark shows which cities can serve as inspiration and that different pathways to a more sustainable urban future exist. Measures to combat the spread of Covid-19 have created a window into a possible future with more space for people, cleaner air and quieter, safer streets”.

The European Union has in place a “Vision Zero” goal on road safety, within which the far away target of close to no deaths by 2050 is touted.

The recommendations

The Clean Cities report wrote that “all cities analysed need to make significant improvements in several areas to have a chance of achieving zero-emission mobility by 2030.”

Local measures aimed at transport decarbonisation can make a profound difference alongside broader improvements, say the authors, adding that these metrics must then be measured in detail in order to track progress.

Cities are encouraged to adhere to a strict timeline for a full transition to active, shared and electric mobility.

Alongside this, the EU and Governments have a strong role to play by reviewing key legislation. On this the report writes: “The EU can play an important role by making zero-emission targets a compulsory element of Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans (SUMPs) in the upcoming update of SUMPs guidance documents. Indeed, the European Commission has proposed that SUMPs become compulsory in the 424 cities that are considered “urban nodes” in the TEN-T Regulation revision according to the 2021 Urban Mobility Framework, hence the importance of making these plans ambitious.13 The conditionality for accessing EU funding upon the development of such plans should also be reinforced